Malaysia Climbing the Rare-Earth Value Chain

Nathan Hu | Raymond Hua Ge

The mass media often frames rare earths as a U.S.–China tug‑of‑war, giving little coverage to the idea that less-industrialized countries can use geopolitics and ESG-conscious capital to climb the value chain. Malaysia, partnering with Australia, shows how to apply comparative advantage economics and sustainability practices to advance in the rare-earth value chain.

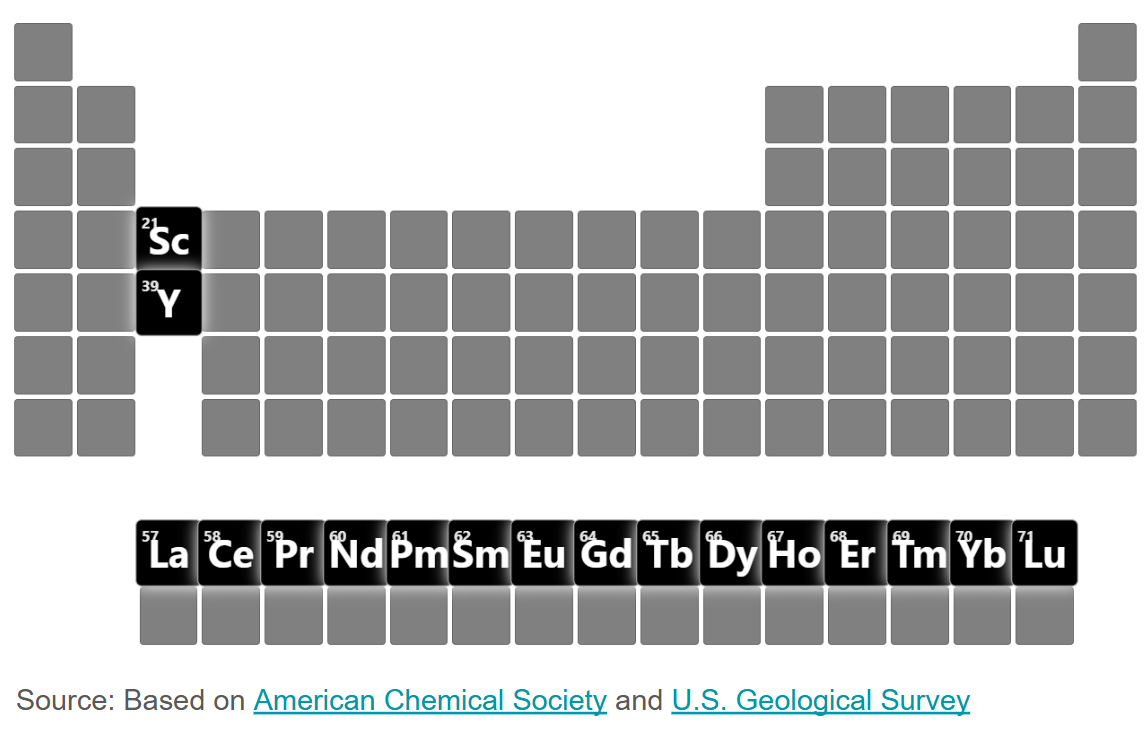

Malaysia has chosen to focus on midstream rare-earth refining, aiming to advance to high-value-added downstream manufacturing while deprioritizing upstream mining. The rare-earth value chain consists of three broad stages. Upstream covers mining and ore extraction. Midstream involves refining ores and separating semi-refined products into individual rare-earth elements, typically in oxide form. Downstream uses rare-earth elements/oxides as raw materials to produce manufactured products such as neodymium‑iron‑boron (NdFeB): permanent magnets for electric vehicles, wind turbines, and communications systems. On the surface, Malaysia may seem to have a comparative advantage in upstream mining given its 16.1 million tonnes of non-radioactive rare-earth elements, valued at approximately $180 billion. If all of Malaysia’s estimated deposits prove economically feasible, Malaysia would rank fourth among countries with rare-earth reserves, behind only China, Vietnam, and Brazil. However, Malaysia’s rare-earth deposits lie beneath rivers and tropical forests, meaning the opportunity costs of mining are far higher. Instead, Malaysia’s cheap energy, abundant water, and an established chemical engineering workforce contribute to its real comparative advantages in midstream rare-earth refining. In contrast, Australia possesses 5.7 million tonnes of rare-earth reserves, ranking sixth in the world, but has limited domestic refining capacity. This complementarity made Malaysia a natural partner with Australia.

In 2012, Lynas Rare Earths (LYC.AX), the largest Australian rare-earth mining company, began midstream refining at its facility in Malaysia. The Malaysia-based rare-earth refinery facility, representing an investment of more than $1 billion, was the first such facility constructed outside China in nearly three decades. It accounted for up to 22,000 tonnes per annum, or about 8% of the world’s separated rare-earth elements at the time, making it one of the largest rare-earth processing plants in the world. Australia supplied the ore, and Malaysia supplied the refining infrastructure and cost efficiencies — a textbook case of comparative advantage driving cross-border specialization.

In July 2025, Malaysia began its rise further up the rare-earth value chain. Lynas and South Korea’s JS Link (127120.KQ) signed a deal to develop a neodymium magnet manufacturing facility in Malaysia. In early November 2025, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim announced that JS Link had purchased land in Kuantan, the same city as Lynas’s refinery plant, for a $142 million neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnet manufacturing facility. With a planned capacity of 3,000 tonnes, the plant will be one of the largest of its kind in emerging markets outside China. Downstream magnet manufacturing captures significantly more value than midstream refining, enabling Malaysia to secure a larger share of profits for its economy.

Malaysia’s midstream rare-earth capabilities are attracting downstream manufacturers, forming an industrial cluster in Kuantan. Industrial clusters — geographic concentrations of related firms and institutions — create agglomeration economies. The proximity of inputs and outputs among firms along the supply chain enables them to reduce logistics costs and supply chain risks arising from transportation delays. The concentration of skilled labor in the city fosters knowledge diffusion, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that entrenches Malaysia’s competitiveness.

Yet, Malaysia’s attractiveness as a rare-earth hub rests not only on economic logic but also on hard-won regulatory credibility. Malaysia developed its capacity to regulate midstream refining industries through painful experience with environmental and public-health failures. A key precedent was Asian Rare Earth (ARE), a rare-earth processing joint venture established in 1979 in Bukit Merah, Perak state, with Mitsubishi Chemical Industries (Japan) as the technology provider and the largest shareholder. The ARE facility improperly stored sludge, a byproduct of its refining process, as residual waste. Naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORMs) such as thorium — an element which remains radioactive for billions of years — exist in ores. In nature, NORMs exist in low concentrations in ores and are therefore harmless. However, industrial processing concentrates NORMs into what scientists call technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive materials (TENORMs): a substance harmful to human beings if exposed in high concentrations. ARE’s improper storage of TENORMs led to environmental contamination of the surrounding area. Community advocates, several media reports, and medical testimony linked this exposure to elevated local rates of miscarriages, congenital anomalies, and childhood leukemia during the 1980s and early 1990s. After years of protests and litigation, the government ordered operations to cease in 1992 and the joint venture was permanently shut down.

Public concern over radioactive waste resurfaced when Lynas began operations in Kuantan, Malaysia, in 2012. At that time, the Kuantan refinery facility performed cracking and leaching using ore transported from Lynas’s mine at Mount Weld in Western Australia. Cracking uses high temperatures and concentrated acid to break apart the ore’s mineral structure. Leaching then dissolves the rare-earth elements into a water-based solution for further processing. These steps produce two outputs: TENORMs, which remain in liquid form and contain concentrated radioactive residues; and mixed rare-earth carbonate (MREC), a solid intermediate product containing multiple unseparated rare-earth elements. The liquid TENORMs are the radioactive residues that residents in Kuantan did not welcome. Public protests persisted for more than a decade.

As Malaysian political pressure mounted, the government used time-bound, conditional licenses as credible commitments to change Lynas’s payoff. Renewal conditions tied to residue management raised the expected cost of retaining those steps in Kuantan. Facing increasing risk that its operating license would not be renewed, Lynas began constructing a complementary facility in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, a 220-mile drive from Mount Weld, in 2021. By 2024, Lynas had commenced cracking and leaching at Kalgoorlie, retaining radioactive TENORMs in Western Australia and shipping MREC to Malaysia for separation into individual rare-earth elements. This renegotiation reflected a recalculation of comparative advantage. Once radiological externalities were recognized, the efficient location for cracking and leaching shifted from Malaysia to Australia.

Australia and Malaysia exhibit complementary comparative advantages across Lynas’s value chain, making the Western Australia–Kuantan arrangement efficient. In Ricardian and Heckscher–Ohlin terms, each location specializes according to its factor endowments.

On one hand, Australia contributes high-quality mineral deposits in Western Australia, where Mount Weld provides the ore, and Kalgoorlie performs cracking and leaching. Both inland sites share the same semi-arid climate, with dry, hot conditions, persistent clear skies, and limited groundwater, which provide natural advantages for handling residues. Cracking and leaching produce two types of waste: water-based waste solutions containing dissolved radioactive materials, and solid tailings. Water-based waste solutions can be temporarily stored in large evaporative ponds lined with impermeable materials at the bottom and sides, where the sun evaporates the water naturally, leaving behind dried residues for long-term storage. Western Australia’s arid climate makes this approach highly effective—water evaporates quickly, and minimal rainfall reduces the risk of overflow or groundwater pollution. Tailings are typically transported via pipelines as slurry—a mixture of solids and water—and deposited in engineered storage facilities. The water in the slurry drains and then evaporates over time, leaving behind solid waste. The dry climate again favors waste management.

Additionally, Australia has a deep talent pool in mining engineering and radiation management. Australian regulators have deep experience in monitoring and enforcing radiation and tailings standards, reflecting the country’s extensive minerals industry. Mining communities in Western Australia are accustomed to tailings facilities, providing the social acceptance necessary to site new storage areas. These attributes make Western Australia well-suited for mining and the cracking–and–leaching stage, where radioactive residues are concentrated and require stringent containment. Cracking and leaching do not create new radioactive material, they concentrate thorium and other radioactive substances already present in the ore. The total amount of radioactive material in Western Australia does not increase. Because MREC represents only a small fraction of the original ore mass, cracking and leaching in Western Australia dramatically reduce shipping volume and costs to Malaysia.

Across the Indo-Pacific, Malaysia contributes different strengths to the later stages of Lynas’s value chain. Kuantan performs solvent extraction and product finishing—processes that refine MREC into separated rare-earth elements or derivatives. These stages require large volumes of chemicals, reliable electricity, abundant water, and a skilled midstream industrial workforce. Kuantan offers all of these at a competitive cost. Kuantan has developed into a regional petrochemical hub, with chemical companies sourcing locally. Kuantan’s location on the South China Sea offers easy port access for exporting finished products to customers in Japan, South Korea, and the United States. Electricity and industrial water are cheaper and more readily available in Malaysia than in remote Western Australia, where infrastructure costs are higher. Importantly, Malaysia is more experienced in handling chemical waste than radioactive waste.

The evolution of the Malaysia-Australia partnership depicts how comparative advantage must be dynamically recalculated to reflect environmental and social realities. The initial arrangement, while economically logical on paper, failed to account for the significant radiological externality associated with cracking and leaching in Kuantan’s humid tropical environment. Through regulatory action backed by persistent public advocacy, Malaysia forced this externality into financial calculations. This sustainability approach led to a more rational and sustainable division of labor. Australia now leverages its vast, arid landscape and deep mining expertise for upstream extraction and residue-intensive processing, while Malaysia capitalizes on its mature chemical engineering ecosystem, skilled workforce, and strategic port access for the complex, high-skill stages of midstream separation.

Malaysia demonstrates that a nation’s factor endowments include not only raw materials and labor but also regulatory credibility, social license, and environmental suitability. By applying ESG principles in industrial policy, Malaysia turned a public health controversy into a source of competitive strength. The country successfully repositions itself from a cost-convenience location to a hub of regulatory credibility, attracting the downstream investment needed to climb the rare-earth value chain. Malaysia’s journey offers a clear and replicable blueprint for how other nations can leverage geopolitics and sustainability to forge their own path to industrial advancement.

Nathan Hu is a freshman at Columbia College studying Economics, with a foundation in research and finance. A published researcher with multiple academic articles in history and psychology, he brings analytical rigor to understanding economic policy and market dynamics. In his free time, he enjoys playing tennis, running, and spending time with friends.