Fatal Flaw: How India’s Reliance on Rare Earth Elements Is Hampering Its Energy Transition

Avery Cotton | Raymond Hua Ge

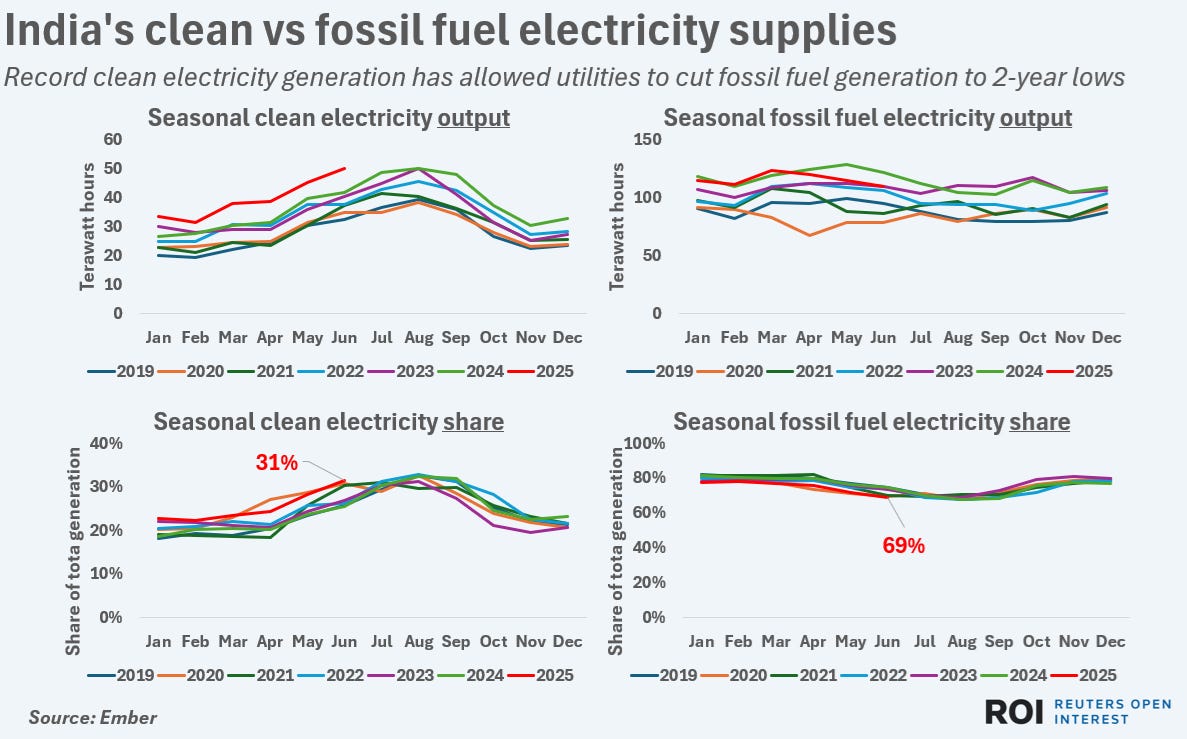

India’s clean-energy transition is promising yet ambitious. To meet its benchmark of net-zero emissions by 2070, the country’s clean electricity generation has skyrocketed, surging 20% in the first half of 2025 compared to the same period in 2024. However, this growth conceals a critical weakness: India imports a majority of its rare earth elements (REEs) from China. Failing to address this gap means India will almost certainly lag behind other powers in the global clean energy race. Elements such as neodymium and dysprosium are instrumental in producing solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries. To reinvent itself, India must streamline domestic policies and increase investment in the mining sector to achieve mineral security, and by extension, energy self-sufficiency.

Figure 1. India’s clean electricity output has consistently risen over the past several years, with clean electricity making up an increasingly larger portion of its electricity generation.

India produces less than 1% of the world’s REEs and relies heavily on critical mineral imports like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. While India has the world’s third-largest share of REEs at 6.9 million tons, the purity and concentration of REE ores are low. Furthermore, the country possesses limited technologies for separation and refinement, leading to higher extraction costs. This places India at a comparative disadvantage compared to other renewable energy leaders. For instance, China controls a hefty 60% of the global mining output and processes nearly 90%. India cannot extract the same value from its deposits using the same labor and capital, exposing projects to global price volatility.

Even as India expands its renewable energy capacity, it remains dependent on China for over 50% of its solar cell and module components. This reliance on Chinese materials calls into question whether or not India can achieve energy sovereignty; unforeseen circumstances can disrupt the entire supply chain. This became strikingly apparent during the Covid-19 pandemic. Chinese manufacturing shutdowns caused India’s solar imports to fall by 77% in Q1 of 2020, resulting in widespread shortages that affected project construction and delayed commissioning timelines.

India’s unique governmental structure causes further bureaucratic headaches. While the central government establishes the legal framework for the mining sector, state governments grant mineral concessions and collect royalties. This complexity often contributes to delays: in 2023, a lithium auction in Jammu & Kashmir was delayed for six months following a lack of exploration data and limited bidder interest. Historically, India’s approach to foreign direct investment has been stringent. For example, until 2023, REE exploration and mining were limited to state entities. Now, private participation in India’s mining industry is legal, though there has been limited interest stemming primarily from high entry barriers and poor incentives, evident in Jammu & Kashmir’s failed auction.

At the crux of India’s REE dependency lies one question: should India prioritize energy independence over the affordability and pace of the energy transition? On one hand, imported solar components remain cheaper and more accessible than domestically manufactured ones, and relying on Chinese supply chains will allow India to deploy its renewable technologies cheaply and rapidly. On the other hand, pushing for self-sufficiency may put the nation behind schedule to reach its climate targets. Ultimately, however, a continued dependence on foreign imports creates geopolitical risk. The India-China border has been contested for decades. After concluding a brief war in 1962, a series of clashes culminated in a June 2020 skirmish in which soldiers on both sides were killed. Coupled with Chinese export restrictions imposed in April of 2025, this shaky detente means that India cannot afford to remain complacent.

In recent years, India has sought mineral security by diversifying its partnerships. In 2023, it joined the Minerals Security Partnership, which promotes sustainable mining practices and stable supply chains. India has also signed bilateral agreements with Argentina and Australia to secure critical mineral supplies. Domestically, India has explored recycling and other strategies to preserve materials from batteries, with startups like Attero Recycling inventing lithium-ion battery recovery processes that could further reduce Chinese import dependence. Both of these create drawbacks: new international partnerships create additional import costs for India, especially over large geographic distances, subjecting the nation to the same weaknesses that exist in its relationship with China. Domestic recycling and similar innovations will require considerable investment and may prove difficult to scale in the short run.

To provide secure access to its REEs and meet its ambitious climate goals, India should follow a threefold approach. First, India should streamline its regulatory landscape, creating a centralized framework for REE exploration, mining, and permitting. This entails delegating responsibilities to the central and state governments, preventing any disputes that could delay project approvals and executions. As a result, India may boost investor confidence and encourage private investment in the mining sector. Next, India should devote greater attention to improving its advanced processing and refining techniques, so that its vast untapped REE reserves can become commercially viable within reasonable timeframes. Third, India should expand its domestic manufacturing of solar and battery components, scaling initiatives like Attero Recycling.

Although India’s clean electricity generation is now higher than ever, becoming truly energy-independent means finding different ways to secure REEs and weaning itself from China. By dissolving regulatory barriers, developing more efficient processing techniques and domestic manufacturing technologies, and improving investor confidence, India can position itself as a true leader in the global energy transition. Achieving energy sovereignty will require India t

o treat mineral security as a priority, not an afterthought.

Avery (CC ‘28) is majoring in Financial Economics and Climate System Science. He enjoys exploring the intersections between renewable energy, environmental policy, and sustainable development, and is particularly interested in how developing nations are navigating the clean energy transition. In his free time, he enjoys birdwatching, playing piano and tennis, and listening to music.