Can India Reverse its Brain Drain Before it’s Too Late?

Amani Dhillon | Sydney Finver

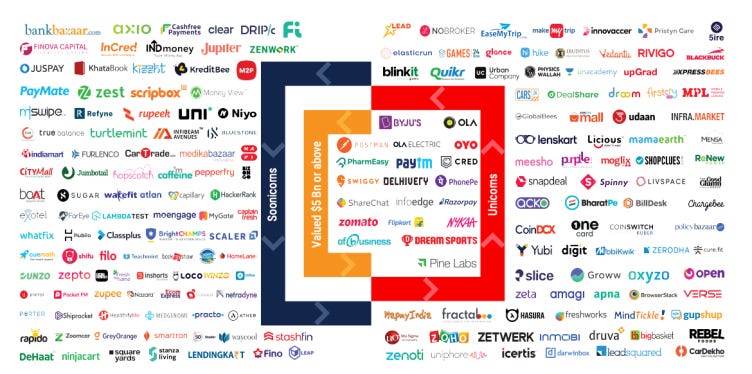

Currently, India is the third-largest startup ecosystem globally, after the U.S. and China, with over 123 unicorns (startups valued at over $1 billion) and more than 600,000 recognized startups as of 2025. However, this emerging market faces a troubling paradox: its top engineers and founders are accelerating innovation abroad, while domestic startups lack the talent retention needed to achieve similar momentum at home.

The nation’s technology startup ecosystem stands at a pivotal moment in its evolution. In the past, the Indian technology market was primarily recognized as a global hub for IT outsourcing. However, the nation is currently poised to redefine its role as a driver of cutting-edge technological innovation. As of 2025, India’s population is nearly 65% under age 35, creating one of the world’s largest digitally native consumer bases. This consumer base allows startups to scale rapidly, especially within fintech and e-commerce. For example, the startup Paytm began as a mobile wallet service but has expanded into a full-scale fintech platform offering mobile payments, financial services, e-commerce, and ticketing. The fledgling company became India’s largest IPO in 2021, and is competing directly with established players like Google Pay and PhonePe.

The emerging startup landscape is supported by initiatives from the Indian government, like Startup India and Digital India, which offer tax exemptions, simplified compliance, and programs to promote digital literacy. These initiatives aim to cultivate an environment conducive to entrepreneurial growth. UPI alone surpassed 10 billion monthly transactions in mid-2023, becoming one of the world’s most efficient and inclusive payment systems. Few emerging markets possess digital infrastructure that is universal, low-cost, and interoperable– a key differentiator for India. Despite this progress, retaining skilled workers remains a persistent challenge. As many of India’s brightest minds emigrate abroad in search of better opportunities and more established markets, the domestic innovation pipeline suffers. India consistently ranks as the world’s largest source of high-skilled emigrants, with over 34 million Indians living abroad. In the United States, Indians receive over 70% of all H-1B visas. Many of these immigrants become engineers, researchers, and founders in the United States, and are key drivers of innovation abroad, instead of at home. However, immigration patterns and visas awarded may be subject to greater scrutiny and changes under the current Trump administration and may also be affected by today’s polarized political climate.

While the decision to emigrate is different for all startup founders, many are motivated by higher compensation and an improved standard of living in developed countries. There are also underlying systemic issues that hinder startups in developing nations and emerging markets. For example, developed markets offer greater access to cutting-edge research facilities and more established corporate R&D. Research spending in India stands at 0.7% of GDP, compared to 2.1% in China and 3.5% in the United States. Startups in developed markets also find it easier to raise large rounds of venture capital because investors trust more liquid markets more. For example, in 2022, U.S. startups raised a whopping $240 billion in venture capital, whereas India only raised approximately $25 billion. Part of the problem is perception: many investors and founders assume that top global roles and frontier innovation happen outside India, reinforcing a “ceiling” that pushes talent and capital toward established markets. Thus, this “brain drain” becomes a vicious perpetual negative feedback loop. As more high-potential talent leaves, the domestic market’s perceived viability and attractiveness decline further, thus driving more people away. The loss of key individuals who could become founders, mentors, investors, or senior leaders severely stunts the growth of innovation. After all, the success of most startups hinges on the novelty of a founder’s idea and their ability to execute that vision successfully within the marketplace.

As an Indian-American, I understand and relate to this dynamic on a personal level. My own family’s story mirrors the broader trend of migration driven by opportunity. Like many others, we left India because the established pathways for career growth, research, and innovation seemed more accessible abroad. Growing up in the United States, I often saw Indian talent at the heart of significant scientific and technological achievements at major companies like Google, Adobe, IBM, Palantir. New Indian founders choose to entrust their ideas to foreign, established markets rather than to home markets. For me, the question of the “brain drain” is not just an abstract set of data, but instead, a personal dilemma. Should founders risk their startup’s potential by staying to contribute to the domestic economy, or should they move to a more established market to give their idea the best possible chance at global success?

India’s challenge is not due to a lack of talent but instead a lack of belief (from investors, institutions, and sometimes even from founders themselves) that global-scale ideas have the potential to be built and managed in India. The Indian market has many advantages that other nations lack: a massive skilled workforce, world-class engineering talent, unprecedented digital infrastructure, and an enormous and eager domestic market. The Indian market can address “brain drain” through sustained investment in research infrastructure, deeper venture capital markets, and an embrace of a mindset that positions India as a global innovation hub rather than just a proving ground. Suppose India can create conditions that inspire founders to stay, not because of obligation, but because of opportunity. In that case, the global narrative will shift, and investors will view the entire market more favorably. When the day comes, Indian entrepreneurs will not need to leave to succeed. Instead, the world will come to them.

Amani Dhillon (CC ’28) is a writer for the Columbia Emerging Markets Review studying Financial Economics and Computer Science. Her academic interests include the intersection of technology and finance, macroeconomic analysis, and identifying the potential of emerging companies in emerging markets.